By: Tom Lounsbury.

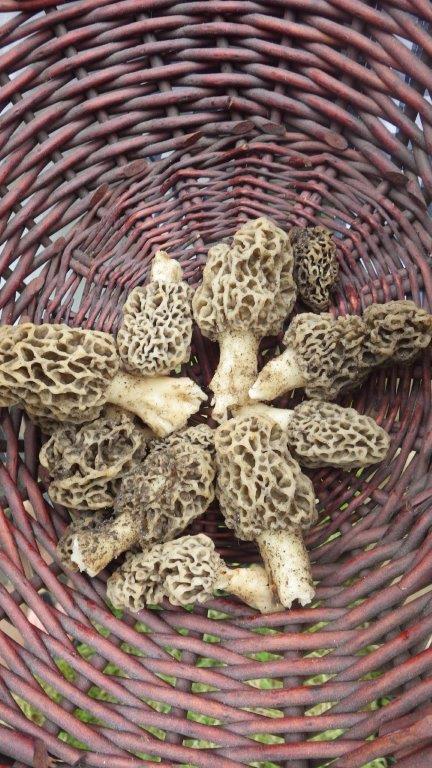

The outdoor pastime of gathering “wild” edible plants goes back to the very beginning of humankind, in order to survive, and it is an atmosphere which truly goes hand in hand with hunting, trapping and fishing (hence the term “hunter-gatherers”). Mushrooms come to mind right away and when it comes to picking springtime mushrooms (of which there are a wide variety), I stick strictly to morels as they are the only edible fungi I’m truly familiar with and comfortable in eating. The fact is, I absolutely love eating morels which have a very distinct flavor that is both earthy and nutty that truly relates to spring. There are two types that I recognize, the black and the yellow, and both types work for me, as well as, to me anyway, taste the same.

Efforts have been made to cultivate morels, but are mostly unsuccessful, because this unique mushroom prefers a natural woodsy environment that is closely associated to trees. I usually find yellow morels associated with deciduous trees, and black morels in a more conifer setting. Because morels can be difficult to find and are probably the most popular mushroom in the world, those sold commercially command a high price, and were harvested in the wild. I saw a quart jar filled with dried black morels that had a $40 price tag, which for an old morel hunter like me, sounded quite reasonable, because I know what it took to collect that many. However, I have yet to ever sell any morels, nor give any away, and am a bit greedy (and very secretive as to where I found them) in this atmosphere.

Morels don’t keep well, although they can be refrigerated for up to a week, maybe. Needless to say folks, morels don’t sit in our refrigerator for very long and the only way to store them is by drying, and why those sold commercially are dried morels.

I have to blame spring turkey hunting on my passion for morels and the fact is, hunting morels and wild turkeys often go hand in hand for me and I’ve found some of my best morel hotspots while scouting for and pursuing the wary big birds here in Michigan. I never hesitate to unload and set my shotgun down to gather a supply of fresh morels.

Of course doing this caused me a bit of panicked grief one time while I was spring turkey hunting on public land near Fairview. One foggy morning after the sun brightened everything up on a heavily wooded hilltop, I quickly discovered that I was sitting in the biggest patch of black morels I had ever discovered. They were here, there and in thick clusters everywhere, and since the gobbler I had been conversing with since daybreak had apparently lost interest and was moving away instead of coming in, my priorities took an abrupt change.

I unloaded and securely leaned my camo-painted shotgun against the nearest hardwood tree and took my camouflage jacket off to create an improvised bag, and I began scrambling around gathering morels here and there on the hillside like a starved squirrel after acorns. In no time at all, my improvised bag was as packed full as it could be. I threw the bag over my shoulder and decided it was time to retrieve my shotgun which I naturally presumed was close at hand, and head out with my bounty. Well folks, natural presumptions can often truly ruin your day, trust me.

It didn’t take me long to realize that the hardwood trees on that hilltop (which were fully intermixed with clumps of jack pines) all looked alike, and my meandering here and there with a total focus on morels, I had become a bit disorientated. I knew where I was, mind you, I just didn’t exactly know where my shotgun was, leaning somewhere in the thick maze of trees. A moment like this tends to be filled with an utter sense of futile panic, and it was readily apparent my camo-painted shotgun became a chameleon, especially leaning somewhere against a drab, moss-covered tree trunk, amidst a whole bunch of drab moss-covered tree trunks surrounded by jack pines.

I took time to take a few deep breathes, settle down and ponder the situation. It was clear a grid search was in order, just like in sorting out a difficult blood-trail. I began the painstaking tree by tree search, using a lightning-struck tree at the top of the hill as an obvious landmark to perform my grid effectively (and I hung onto my camouflage bag of morels, as I didn’t want to lose that too) and I eventually found my shotgun, but not until a heart-throbbing hour or so later. The fact it was doing such a good job blending in, I almost moved right on by, and I had to do a double take to make sure I wasn’t seeing things in a tree trunk gray and mossy green atmosphere.

I gave my shotgun a smooch like a long lost love, and I have ever since kept my camouflaged turkey guns (unloaded of course) leaning only briefly against a tree real close by, whenever I get sidetracked while gathering morels.

There certainly are times when I frequently go into the woods to solely hunt for morels and it is a favorite springtime pastime for quite a lot of folks in Michigan, who are generally a bit secretive. Avid “gatherers” tend to be that way about their favorite spots. It is what it is.

Several springs ago, my son Josh located the first morels on the family farm (which contains a relatively young and continually growing “woods” that I planted myself over the years). They were the big and plump yellow variety and I was highly elated to know such was real close at hand. Josh has continued to find more each spring which lets me know they are spreading, much to my delight. Then there was the large patch of morels Josh discovered, but it was intermixed with poison ivy.

Poison ivy and I don’t get along together at all, and I even start itching just thinking about it. Needless to say, that was the most unmolested patch of morels ever. It was my hope that those particular morels sent out plenty of spores to propagate, which may have happened. A couple springs ago I discovered a large patch of yellow morels in the apple orchard right next to our house. This turned into being the most convenient morel-picking moment I have ever experienced, and with some grandchildren on hand as well. There was also a ready supply of wild asparagus in a nearby fencerow, and my son Josh, being a gourmet cook, prepared a dandy morel and asparagus dish in cream sauce that was out of this world, and it went well with grilled venison chops.

Another woodland delicacy I would like to see growing on my farm but haven’t as yet, is the wild leek. This wild onion species of the eastern woodlands has other names such as wild garlic and it is more popularly known in the Appalachians as ramps. In fact it is so popular there are even ramp festivals in some southern states. It is also so popular in some areas such as Quebec, that it has been put on the endangered list there. Chicago is actually named after this flavorful plant, from a Native American word for wild leeks that is “chicagou”.

I have my favorite local wild leek hotspots and it is an easy plant to identify with its broad green leaves and burgundy lower stems which grow in low, dense clumps. I use a small garden spade to easily bring up the clumps of bulbs that smell a lot like garlic but taste more like a mild-flavored onion (at least to me). The entire plant is edible and I especially like dicing up the bulbs and frying them with morels, a very unique and distinct springtime flavor. Wild leeks are also very excellent when battered and deep-fried, and I like to eat them raw in salads.

I’ve been known to nibble on wild leeks whenever I find them while turkey hunting and my wife Ginny can always tell because I come home with a bad case of “garlic breath”. They do have a lasting effect in this manner, but I truly do love wild leeks which to me are way more flavorful than the garden variety.

As with the morels, I keep my wild leek locations all to myself, because, like I mentioned before, we woodsy-type “gatherers” are usually a secretive and bit stingy lot.

- Murphy Lake’s 16 th Annual “Pike Pull” ice fishing contest - February 22, 2026

- Enjoying Wintertime bushytail hunting adventures - February 2, 2026

- Dealing with The Big Chill - January 27, 2026