By: Tom Lounsbury.

By: Tom Lounsbury.

I must admit that I have a strong passion for reading, and when it comes to reading material, I have a real soft spot for that relating to history and if it entails matters associated to the outdoors as well so much the better.

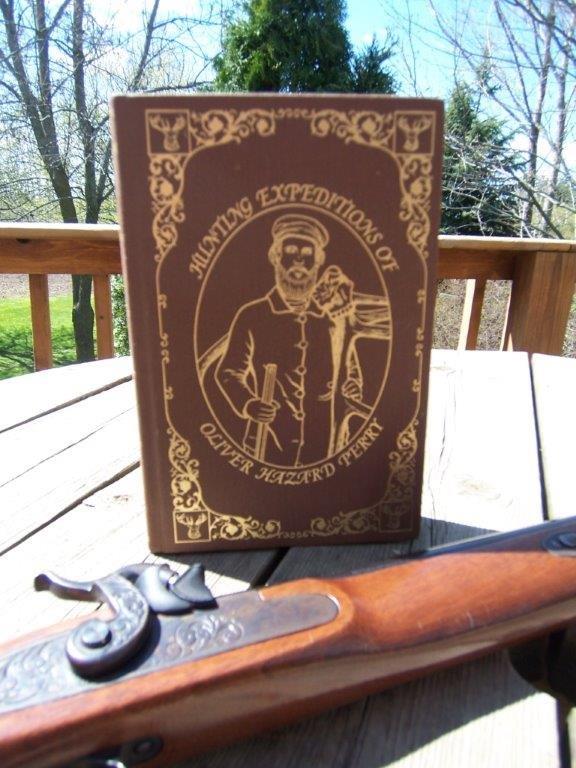

I came across a real jewel some time back, “The Hunting Expeditions of Oliver Hazard Perry”, based on his hunting diaries from 1836 through 1855. An article in an outdoor magazine brought this literary work to my attention, and I first located it through my local library. After reading it, I knew I had to have my own copy in my personal collection. I did this through Barnes and Noble, and money well spent in my opinion. (Today the stockpile through regular bookstores has dried up, and the book is now available through online sources with a price tag that keeps climbing – so I made a wise investment).

It is the only reprinting (1994 by St. Hubert’s Press) of a very rare piece of which only 100 copies were made of the original book in 1899 (I saw one of these rare copies was for sale online for $2000). Perry was killed in a railroad accident in Ohio in 1864. His detailed hunting diaries would be stored away until they would fortunately be discovered by his niece in a chest in the attic more than three decades later, and the limited printing of the original book was not meant for sale, but for giving only to family and friends.

Perry’s words clearly give us a view into the hunting style, equipment, and atmosphere of a time long gone, and no other published historical work does it so well. The areas reflecting his hunts are at first for whitetail deer near his home in Cleveland, Ohio, and then later for elk, deer, and black bear in the pristine wilderness found along the Cass River in Michigan’s Thumb area. Myself being a lifelong Thumb resident who grew up not far from the Cass River, I take very special interest in this part of the book.

Some chapters can truly define a book, and my favorite in this work is “Elk and Deer Hunt in Sanilac and Tuscola Counties, Michigan, 1852”. Needless to say I must spill the beans on the content of this chapter in very abbreviated form to give you an idea of this book’s value to history and the critical insight it has into how things were when hunting in times long gone by.

Perry would board a steamboat from Ohio to Detroit on September 6th. His hunt, including getting there and back, would entail more than 2 months. Another steamboat would take him and his gear and supplies to Port Huron, and a third steamboat would then take him to Lexington. His traveling and hunting companion on this particular hunting expedition was Frederick Deming.

Perry and Deming go by ox cart from Lexington on the first leg of their journey to Elk Creek, but as the trail narrows and the ground roughens, everything is transferred to a sort of Indian travois made from a tree limb with a large crotch that holds the supplies and is pulled by a pair of small but tough “Indian ponies”.

(I take special note of this, because it is often assumed the Native Americans in the Great Lakes area traveled only by foot and canoe. Certainly these were primary modes of travel due to the dense habitat, but where possible, horses often did play a role).

Perry and Deming would set up a base camp on Elk Creek, and with minimal supplies in knapsacks and the clothes on their backs, they would begin an arduous trip on foot to reach the Cass River. While they had a few days’ ration of pork and “hard bread”, they planned on living off the land as their primary source of sustenance. This was the era of the caplock muzzleloader and Perry carried a doubled barrel .45 caliber rifle (that weighed 11 pounds), and Deming carried a double barrel shotgun. This was also clearly a wilderness experience in which they used a compass and a somewhat limited map, and if anything went wrong they were definitely on their own. Some nights were spent close to their campfire listening to the vicious snarls and growls of unknown animals prowling nearby in the darkness.

The forest entailing giant, ancient trees was so immense that the pair of intrepid hunters would often have to climb a tree to get a compass bearing on a particular landmark. This is how they located a small slice through the cover and made a heading for it.

They would encounter a small, unnamed stream that by the direction of the current, they knew it would lead them to the Cass River. It was while following this stream that they heard the bugling of bull elk and stalked in on a herd of them. Perry would shoot a huge bull, using both barrels of his rifle to put it down. There is a photograph in the book of Perry holding the antlers from this “Thumb” bull over his shoulder, posing with them after returning home. It is clear the bull elk taken in Sanilac County was a bruiser, but it is difficult to tell how many points it has in the photo. A drawing of the antlers with Perry’s double barrel rifle lying across them shows they are an enormous 8 x 8 set with an unusual crown on each side.

While retrieving elk meat and not carrying his rifle, Perry would encounter a large pack of wolves drawn in by the scent of the kill. What is truly unique is that all the wolves were jet black. Although black timber wolves are not rare, neither are they, I believe, a common feature. Seeing an entire pack of this color makes this a very remarkable encounter. Needless to say what elk meat Perry and Deming couldn’t carry away wasn’t going to waste according to the wolves.

Once to the Cass River and by this time living solely on jerked elk meat and thorn apples (and a berry he calls “pigeon berry”), Perry and Deming made their way downstream to an Indian encampment called “Indian Fields”, near present day Caro. There, they stayed for a while with a pioneer family named Bigelow to recuperate, eat bread and potatoes, and repair their tattered, woolen clothing torn up by the rigors of negotiating across the nearly impassible Thumb wilderness.

By this time it was mid-October and Indian groups from other encampments such as See-bee-wane (Sebewaing) and Qua-na-cussee (Quanicassee) gathered at the Indian Fields for their annual fall hunting powwow. The celebration was such that Perry and Deming purchased an Indian canoe (due to the beating this craft could take according to Perry’s notes, I believe it was a dugout and not the birch bark version – but he doesn’t say) and paddled upstream to make camp in a quieter atmosphere, and to hunt deer.

During their stay they encountered 3 elk hunters coming downstream by canoe that had been hunting along the North Fork of the Cass River (near present day Cass City). Minus any elk, the 3 hunters had had more wilderness experiences than they cared for and were paddling back to Saginaw. Although they had encountered plenty of elk, (no wonder the township in the area they hunted is called “Elkland”) the forest was so dense that trio of hunters had trouble stalking in close enough for an accurate shot. They were quite stunned by the size of Perry’s elk antlers.

Perry and Deming would eventually have to paddle to Saginaw themselves, passing by the small pioneer settlements of “Vasser” (Vassar), Tuscola, and “Dutch Town” (Frankenmuth).

Once to Saginaw, arrangements were made to go by Lake and retrieve their equipment left at their base camp on Elk Creek, and then return home.

The end of the chapter features the distances Perry and Deming hiked on the Cass River hunting expedition, such as noting the bull elk was killed 8 miles from the Cass River. It also mentions the distance between the forks of the Cass, as well as the distance along the river to various pioneer settlements and Indian encampments. Included is the detailed list of supplies hauled in for the 2-month stay in the Thumb’s wilderness, as well as the technique used by Thumb area Indians to brain-tan a deerskin.

I’ve canoed the Cass River countless times since childhood, including both forks, and I have paddled downstream as far as Frankenmuth. I’ve often wondered about the history, wild animals, and people associated to its meandering current.

Reading Oliver Hazard Perry’s written and very detailed account sheds an informative light on it all and I thoroughly appreciate the fact he took the time to accurately document everything in his diary each day, using the stub of a pencil and the mellow, dim light from a crackling campfire.