By Tom Lounsbury.

By Tom Lounsbury.

When April arrives I automatically develop a case of “wild turkey fever”, an annual spring malady that has been afflicting me for almost 50 years now. I find myself habitually sorting out turkey hunting gear, practicing with various turkey calls (when I do this indoors it eventually nets a rather blunt complaint from my wife) and patterning my turkey shotguns, of which I have a few favorites, at my backyard shooting range.

Although I already know how each shotgun patterns, I need to assure that I am still in tune with them, and I practice shooting from various sitting positions that I would use in the field, as well as I practice “switch-hitting” (being right-handed, I also practice shooting left-handed and by partially closing my right dominant eye, my left non-dominant eye takes over for aiming). Turkey gobblers can suddenly appear in range from the least expected direction, and switch-hitting has allowed me to successfully bag gobblers I might otherwise not have had a shooting opportunity at due to the awkward and “wrong side” angle.

Patterning a particular shotgun and the selected load that is going to be used for turkey hunting is actually quite crucial and is very similar to sighting in a rifle for big game hunting. The key being that the center of the shotgun’s pattern properly entails the critical head/neck area of life-sized turkey targets (which are readily available these days). This is done at various yardages to confirm the actual range effectiveness of the shotgun and its particular load that is going to be used in the field. For a fact, any shotgun can be used for turkey hunting as long as the user fully understands the strengths and weaknesses of that particular shotgun (and load) and has confidence in it. I know several instances of youth hunters using a petite .410 bore to drop large turkey gobblers dead in their tracks.

A favorite turkey shotgun of mine I’ve used for many years is an AYA 12 ga side by side double barrel, with a right modified choke barrel and a left full choke barrel, and each barrel has bagged gobblers, with the modified barrel bagging the most (this shotgun was too shiny and “pretty” for the turkey woods, so I painted it olive drab green). It is chambered for only two and three quarter inch shells, with my favorite being Winchester (ounce and a half) copper-plated lead number fives. This is actually my favorite pheasant hunting combination which does equally well for putting tough and tenacious gobblers down for the count.

What has always worked for me is what I call the “30 yard rule”, which means I never try for a shot at a gobbler unless it is very near or inside of 30 yards (my longest kill-shot thus far is 32 yards, with the majority of birds being taken at well under 30 yards). My goal is to call the gobbler in as close as possible (a very thrilling process) and I always aim at the turkey’s neck where the feathers join flesh, thus I am fully utilizing the shotgun’s pattern to also entail the head. This 30 yard rule eliminates any “ifs” and helps to avoid wounding turkeys, which can readily happen when birds are out there a bit at “guesstimated” longer ranges.

Truthfully, there is fantastic turkey ammunition available today (the best ever), and outstanding “turkey chokes” which when combined offer amazing long range performance, and in excess of 50 yards. It does however ethically require the turkey hunter to fully understand the shotgun and load performance at those longer ranges, and be able to accurately gauge those yardages. Specialized turkey ammunition can also be costly, as I’ve seen some that were as much as $5 a shell. However, being old school, I’ll stick to my 30 yard rule and truly love the challenge of calling gobblers in close, no matter what ammunition/choke combination I’m using.

My most spectacular miss was on a gobbler that was actually “too close”, being less than 10 yards away when he silently and suddenly stepped into view. I was using my 20 ga Remington 870 pump-gun fitted with a super tight turkey choke, and stoked with potent 3 inch turkey loads (trust me folks, today’s turkey shotgun chokes and turkey loads maintain very tight patterns as is advertised). It was a dandy gobbler and he became immediately suspicious about the large “lump” sitting at the base of a tree, and he was bobbing his head and neck around for a better sight angle, and my tight shot-charge completely missed him. This is when a more open choke would have been preferable, and the gobbler had speedily whirled in a blur and disappeared before I could rack in another round. Needless to say I had abruptly changed his attitude for the moment anyway, of wooing any lonesome hen turkeys (encounters like this go a long way in educating surviving gobblers and I’ve known some pretty “hunter-wise” birds that were very difficult to hunt).

Probably the most daunting matter for most new turkey hunters is the calling factor. When I first ventured into Michigan turkey hunting, I had to special order my turkey calls because none were stocked on the shelves, but that all changed when turkey hunting began to quickly gain in popularity. Now, you name it and it is available with something always “new and better” coming out. There are also marvelous instructional DVD’s (and books) on how to call. My personal favorites are the old-fashioned friction type such as the box and slate calls. I’m one of those “if it works, why change it” sorts.

The wild turkey in Michigan is certainly a successful conservation story. I can remember when the only turkey hunting opportunities available during the late 1960’s and well through the 1970’s was in the northern Lower Peninsula. But the wheels were in motion in releasing the birds statewide and the first wild turkey transplants occurred in the Thumb during the mid-1980’s, followed by the Thumb’s first spring turkey season in the early 1990’s. As a result you don’t have to travel far in Michigan to find good turkey hunting opportunities today, and I truly appreciate this fact. Although I plan to travel to other parts of the country to hunt the other subspecies, I’ve thus far only hunted Michigan’s wild (Eastern subspecies) turkeys, and I have no complaints at all. It is great hunting!

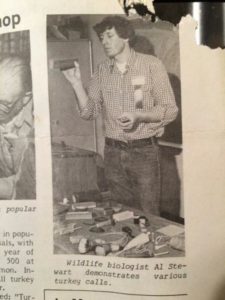

The best wild turkey expert I know not only per Michigan, but nationally as well, is MDNR Upland Game Bird Specialist and Program Leader Al Stewart. He’s been a MDNR Wildlife Biologist for more than four and a half decades and has played a major role in helping Michigan become one of the best turkey hunting states in the country. During the 1970’s he helped host turkey hunting workshops throughout the state for new turkey hunters. He is also the only person in the world to capture and release a “world slam” (all subspecies) of wild turkeys for restoration or research and has been nationally recognized by the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF) and the turkey conservation community for this contribution.

The best wild turkey expert I know not only per Michigan, but nationally as well, is MDNR Upland Game Bird Specialist and Program Leader Al Stewart. He’s been a MDNR Wildlife Biologist for more than four and a half decades and has played a major role in helping Michigan become one of the best turkey hunting states in the country. During the 1970’s he helped host turkey hunting workshops throughout the state for new turkey hunters. He is also the only person in the world to capture and release a “world slam” (all subspecies) of wild turkeys for restoration or research and has been nationally recognized by the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF) and the turkey conservation community for this contribution.

Al Stewart is also an avid turkey hunter and has hunted from Maine to Mexico and successfully bagged a “world slam” (all the wild turkey subspecies) as well. His favorite turkey shotguns are a 12 ga Remington 11-87 and a 12 ga L.C. Smith side by side double-barrel. He prefers a modified choke because the only turkeys he has ever missed have been while using super-full turkey chokes, and he also uses the 30 yard rule and has found the modified choke works fine for him in a more forgiving manner in regards to its wider pattern.

He prefers number 5 or 6 lead birdshot, and copper-plated is fine, but not necessary. Al is purely into head/neck shot-placement, and calling birds in to 30 yards or less. Although wild turkeys can be shot at longer ranges, he has seen far too many turkeys crippled with “long shots”. Birds hit with some pellets can later die, and sometimes not until weeks later.

When it comes to calling in wild turkeys, Al’s favorite calls are mouth diaphragms because they offer a wide range of vocalizations and are hands-free, although he is proficient with all turkey calls. His favorite place to hunt wild turkeys is in fact Michigan, because it offers some of the highest quality turkey hunting opportunities of any place in the country.

The wild turkey is truly a superb game bird which is unique to America. It has excellent eyesight and color perception (the reason wearing camouflage from head to foot is a wise idea), and outstanding hearing capabilities. It can also run quite fast and when required, it can flush and fly away like a grouse (albeit a very big grouse). I’ve read that if wild turkeys could smell (which fortunately for us they can’t) hunters would never be able to kill any. I can state after many years of experience in pursing wild turkeys, no truer words were ever written.

There is nothing quite as spectacular or breathtaking as a wild gobbler with its snow-white skull cap, powder blue cheeks and scarlet red throat, and iridescent feathers glistening in the sunlight. There is something very satisfying and thrilling about calling a gobbler into range and watch as it fluffs up, fans its tail and literally struts in ever closer. The springtime woods and atmosphere truly add a distinct accent to the entire scene.

Yep folks, I definitely have a bad dose of wild turkey fever right now and I know of only one cure. I’m glad that very special cure is fast approaching now that April has finally arrived.